Essential Worker - Invisible No More

- Chapman & Roberts, P.A.

- Sep 3, 2020

- 7 min read

The Greatest Generation

President Roosevelt called December 7, 1941, a day of infamy, and it was. However, it also led to the greatest mobilization of manpower, industrial production, and concerted national effort that the United States has ever seen. Millions of US citizens joined the Armed Services and fought in two immense theaters (Europe and the Pacific) against powerful enemies who had seized the initiative in a struggle for world domination. It took four years and the ultimate sacrifice of millions of soldiers and civilians to win that fight.

Every Memorial Day, we pay tribute to the men and women of our Armed Forces who paid that price to keep the world safe from tyranny and despotism. They are rightly honored as the brave and courageous protectors of freedom, the greatest generation.

Mexican Contributions

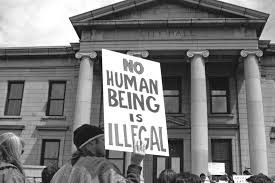

As we honor them, we do so perhaps without thinking of the many Mexican men and women who worked in the fields of the Southwest US, to keep our food supply intact during that brutal four year period. Today, with the threat of the global pandemic, we belatedly recognize Mexican and other foreign nationals working in the food industry as essential members of our COVID-19 workforce, along with other essential workers in health care, transportation, construction, home and business cleaners, and many other industries. Some of these essential workers are now US citizens and permanent residents, but millions are undocumented workers.

They should not be undocumented any longer.

Why Change the Law Now?

The COVID-19 crisis has changed virtually our entire way of life. We cook, travel, attend school differently. We mark the birthdays and anniversaries of family, friends, co-workers remotely. We watch burials remotely, too. The sense of loss is universal and palpable.

With this crisis in full sway, why should we start a national discussion about an immigration issue that is likely to lose urgency when the economy comes back? Why should we ask Congress to address an issue that does not affect Americans?

These questions may sound logical, but they are based on incorrect assumptions: the discussion has been ongoing for over 20 years, and the issue unquestionably affects all Americans.

Change that takes us back to 1942

The historical background goes back to the early 20th Century. From the early part of that century until the late 1990’s, Mexico sent its young men and women into the US to harvest US agricultural products. That migration was truly seasonal, and represented the intersection of immigration with the economic law of supply and demand. Mexico had a large supply of qualified workers; the farms in the Southwest US had an unfilled demand for them. This seasonal migration continued uninterrupted for decades and served both countries reasonably well.

By early 1942, the war effort demanded that millions of US men and women leave their jobs and join the military. They did that, and many of the jobs held by US men were filled by their spouses or went unfilled. During the war, the Mexican men and women farmworkers who previously had entered the US in an informal way, were able to enter the US with legal status for the first time under what was called the Bracero Program. Congress created it in 1942 in response to WWII, and it continued until 1964 as the Vietnamese conflict was ending. During that 22 year period, the number of Mexican nationals entering the US illegally dropped from about one million to about 40,000 per year. That’s forty thousand. Many US Border guards could not find anyone to arrest, because virtually all Mexican nationals entered legally.

The end of the Bracero Program

In 1964, Congress ended the Bracero Program. It did so because of continued objections from powerful farm owners in the Southwest, as well as objections from Cesar Chavez who founded the union that became the United Farm Workers (UFW) and staged a nationwide lettuce strike. Very strange bedfellows. The farmers detested federal intrusion into their business; Chavez hated the poor implementation and oversight of the program. Just as Congress was passing sweeping civil rights legislation, it terminated the Bracero Program.

Since then, for over 55 years, our immigration system has not included a temporary visa for workers who perform manual labor, in year round jobs.

But not the Law of Supply and Demand

Rescinding the Bracero Program, however, did not have any impact on the law of supply and demand. In fact, in the years immediately after Congress cut the program, the number of illegal entries from Mexico shot back up to about 950,000 per year, and they remained relatively constant for the next several decades. And, as the years have gone by, the demand for such essential workers has spread into all segments of the economy to include a wide range of year-round jobs. As our schools have produced more and more highly educated workers, the domestic supply of essential workers has declined proportionately. The demand side of this equation has only increased.

But rather than create a work visa for these essential workers to match the constant demand for their services, Congress opted for enforcement-only legislation. In 1996 it passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRARA). That law created “bars” that apply to people trying to enter the US in three situations:

A person who has been in the US without permission for more than 180 days, but less than one year, and then leaves the US, is barred from legally re-entering for 3 years (unless a waiver is obtained).

A person who has been in the US without permission for one year or more, and then leaves the US, is barred from legally re-entering for 10 years (unless a waiver is obtained).

A person who has been in the US without permission for over a year and leaves voluntarily, or leaves under a deportation order (regardless of time in the US), and then re-enters without permission, or even tries to do so, is barred for 10 years with no possibility of a waiver.

Unintended Consequences: Keeping Undocumented People in the US

These new procedural rules in IIRAIRA had one over-riding purpose: to keep people without documentation out of the US. But they have done just the opposite; the undocumented population has swelled since IIRAIRA, because they know what will happen if they leave. Congress naively believed that this new immigration law could preempt the economic law of supply and demand, but that goal was unrealistic at best. In addition, instead of keeping these workers out of the US, it has kept them inside our borders. As the years have shown, enforcement-only policies do not work.

Why Don’t They Follow the Rules Like Everyone Else?

We hear the constant drumbeat of pundits and politicians who claim that “these people” should follow the laws, just like everyone else. Well, they would, if there was a visa category that they could use to enter legally.

But there isn’t one, not since the Bracero Program was terminated in 1964. Unlike high skilled workers who can enter the US to work in year round jobs with multiple kinds of visas, essential workers who perform manual labor have no temporary visa by which they can enter the US, with one exception: the H-2 visa for seasonal agricultural and non-agricultural workers.

But the US economy does not rely solely on those seasonal workers, and the true demand for year-round manual workers has only increased.

COVID-19’s Impact on the Economy

We need to recognize that demand for labor has been warped by COVID-19, and a broadscale recovery is months away. A fair question is whether these essential workers are really necessary as our economy recovers. Another fair question is whether the particular circumstances of certain undocumented groups require us to approach their status on non-economic terms. For instance, if young people were brought to the US as infants (“DACA’s”), and, if they have a clean criminal record, and they have obtained a high school education or volunteered for the military or been working for, e.g., over 2 years and have an employer who will provide them with a job; with those qualifications met, should we allow them to have a temporary visa status (DACA is not a visa; it is an administrative program)?

For others who have been here only a short while, should they have the chance to obtain some kind of a temporary work visa? Employers who need workers to fill year round jobs for 2 or 3 years -- should they have the chance to sponsor those new workers for temporary work visas just like employers of highly skilled workers?

Likewise, should we allow a person to remain here who has a serious criminal record or poses a threat to US national security? What if the criminal record was generated over 15 years ago? 10? 5?

Why President Reagan Got It Wrong

Some of these decisions will be hard to make. Some people have made great contributions to their communities, and some have not. Some have US citizen spouses and children who are now adults and can support their parents. But just because making a decision is hard is not a reason to refuse to make it; in fact, the passage of time has just made this issue more difficult to solve.

But the solution is not simply the one that President Reagan signed into law in 1986: that law gave some 3 million undocumented people the chance to obtain permanent resident status. Although widely praised, it failed to address the core reason that so many undocumented people were in the US then and are in the US now: the lack of a temporary work visa for essential workers who fill manual labor, year-round jobs (jobs filled by those we now, finally, recognize as “essential workers”).

The law of supply and demand functions fairly well in almost all areas of our employment-based immigration system. The one clear exception involves essential workers. Until now we could ignore them, or say they were not essential, or “they should just follow the rules like everyone else.” In the world we inhabit today, we cannot ignore them, they are essential, and since 1964 there have been no rules for them to follow.

When will Congress Get it Right?

Since the late 1990’s, immigration advocates have explained the nature of this problem to members of Congress repeatedly, in meetings in their offices each spring in DC, and in their home district offices throughout the years. Their stock response has been “I am ready to work across the aisle.” Translate: “I will not do anything about this issue, because a strong stand on it could lose me votes in the next election.”

What will it take for Congress to have the courage, the common decency, to do its job? Will it take deporting young nurses with DACA who are caring for COVID-19 patients at Cone Hospital in Greensboro? Deporting essential workers who clean our homes and offices? Deporting essential workers who support the entire food chain, from farm to table and every job in between?

Maybe this crisis will give cover to Congress to do what is moral, what is right, and what simply reflects common sense. Or maybe we need to elect candidates who have the courage to do the right thing by these essential workers (and their employers) who no longer should be treated as disposable or invisible.

- Gerry Chapman